AWAKENING NEW YORK

In a red light moment on 75th St.

The cars stood still.

And I, in the lingering fumes,

Beneath the oak leaves

Gasped.

Waiting beside me (for the

red light to turn green)

Blue morning glories,

Bloomed in radial profusion.

Their vines turning always to

the right.

Around the black iron fencing

Heart shaped leaves

Suspended above judgment

Growing in their own space, a

sanctuary,

Breaking through traffic

jammed

existence.

Who planted these?

c. 2000 Mym Tuma

|

|  |

In 1997, I published An Artist's' Odyssey, a book about my life as an artist. In one defining section of it, I undertook to explain the relationship I had with Georgia O'Keeffe, a woman fifty years my senior and known and adulated for her daring in her life and work and her enormous talent as an artist, I wrote:

. . .we had shared similarities . . . we saw beauty on earth, in pebbles, rock formations, or clouds, space, flowers, hills, mountains, bones and shells as more than the realistic objects in nature.

What I was saying was that the kinship we recognized between us came not just from both of us thriving in "wild" or natural settings - she, for years, in New Mexico, in her home in Abiquiu, near the Continental Divide, in the high lands towered over by the San Juan Mountains; I, at the time I first met her, along the Pacific Coast, near Stanford, later in Guadalajara, Mexico, where I had my outdoor studio. Rather, it was because, each of us in her own way, had found a means of translating the excitement, the exhilaration of being thrilled by nature's power, variety and fecundity into a personal artistic metaphor. That "metaphor" became the signature of each of our creations: Ours differed. But the fact that each of us understood the other's and the fact that we acknowledged the dissimilarities, as well as the consonances, in our styles, further fueled our union, our association, and led us to know and experience each other's company for a period of some seven years.

Why did I first come to meet Georgia O'Keeffe, the famed icon of American female painters? Why did this painter of the bleached cattle skulls and bones remaindered on the high desert invite me into her home and studio? So begins our story:

At twenty-five, I was a newly graduated scholarship student, boasting an M.A., from Stanford University's program in painting. My thesis had been an immense mural tacked up on the wall of a studio garage I rented. I called it Tedium Vitae, meaning, the "Tension of Life," and in it I had tried to gather and depict what happens along the California Coast when the energies of land, sky and ocean meet and proudly thunder in their union. And I was proud of my work, knowing the effort and dedication I had pledged to it, and convinced therefore, that it had sealed and signed and launched me off into a lifetime career and commitment as an artist.

Feeling thus high, happy with what I had created, fully believing that my artistic strengths were waiting for an opportunity to be explored and developed, I can now understand my reaction when I looked at some photographs of O'Keeffe's home in Abiquiu, New Mexico, and of her art, in the April, 1963, issue of House Beautiful magazine

1. How inspiring, I thought, to live in those mountains! How well O'Keeffe understood how to capture the rugged strength of the land she lived in - as well as the breathtaking beauty of the flowers and growing, living things of the strenuous high desert land her home was set in.

Here is a woman, an artist, who shares my excitement with nature! What if she is fifty years older and celebrated for her work! I'm sure she would like to talk to me: that we can find common ground in examining our philosophies and callings as artists. Such was my naive confidence at age twenty-five. So I wrote her: May I come out to visit you? Happily for me, she responded: Yes, do come. [Thanks for your page!]

Thus began a string of visits to Georgia O'Keeffe that lasted through the summer of 1971. Much of what transpired in my stays at her house in Abiquiu, New Mexico, is told by the correspondence that I am reproducing. One impression that I believe the reader will garner from reading these letters is the care and effort she, Georgia O'Keeffe, took to support my work. Her handwritten letters tell of this encouragement: "Do not sell your car . . . I will send you the two thousand that you need to get your next three paintings done . . ." (7/3/68)

2 - Enclosed find check . . . I hope you are well and can be at work." (7/27/68). That I be at work and free in my mind not to be distracted by financial matters was a stance she took in speaking and writing to me.

Importantly, in our meetings and conversations, when I turned to her to discuss my work and gain her opinion, she underlined her belief that, yes, I would succeed as an artist, especially because of my willingness to work so hard and to safeguard the talent I had by remaining true to my vision of how i could express, as a painter and sculptor, my grasp of nature's might and my appreciation of all that I have been privileged to view lying ahead of me in my sight.

The issue of money, from Georgia O'Keeffe to me, comes up frequently in this correspondence. Why did she send me money? What obligations or circumstances were attached or understood or made explicit in these checks to me? I think I may fairly say and characterize these checks through this overriding explanation: Miss O'Keeffe voiced the belief that she understood how needy I was during this stage of my life. (Most of the time, I lived in a magnificent studio, near Guadalajara, Mexico: "Magnificent" because its location afforded me the opportunity to be near and study the rocks, minerals and living things that fed my art. Its economic reality was that it had neither electricity or running water. She wanted to encourage me to continue doing my "sculptured paintings" and pastels, believing, in time, that I would assemble enough of these to have an exhibition and to sell many of my works.

So, she proceeded in this way. One of my works --

Obsidian -- she bought outright for two thousand dollars, and brought into her home in Abiquiu. She knew, at Mexican prices and because of my frugal style of life, how many months of artistic creation that would afford me. Another,

The Bud of the Flowering Tree , she considered would eventually be a sale item; so she advanced me another two thousand against that. When I, not too long after that advance, did sell a major work -- the Form or Sculptured Painting,

Moonseed, to the Hirshhorn Collection, in Washington, D.C., for one thousand dollars, through the help of her business agent, Doris Bry (who, for a while, acted as my agent, also) -- I sent a check for one thousand to Ms. O'Keeffe. Our other financial dealings are referred to in our correspondence.

So, she proceeded in this way. One of my works --

Obsidian -- she bought outright for two thousand dollars, and brought into her home in Abiquiu. She knew, at Mexican prices and because of my frugal style of life, how many months of artistic creation that would afford me. Another,

The Bud of the Flowering Tree , she considered would eventually be a sale item; so she advanced me another two thousand against that. When I, not too long after that advance, did sell a major work -- the Form or Sculptured Painting,

Moonseed, to the Hirshhorn Collection, in Washington, D.C., for one thousand dollars, through the help of her business agent, Doris Bry (who, for a while, acted as my agent, also) -- I sent a check for one thousand to Ms. O'Keeffe. Our other financial dealings are referred to in our correspondence.

And so, the correspondence follows. The players who are both the writers of it or the actors referred to in it are Georgia O'Keeffe, age 77 when I first visited her; I, Marilynn Tuma; Doris Bry, O'Keeffe's agent and, until a separation of ways they had when O'Keeffe was well into her eighties, a close personal friend and companion; Jean Seth, the owner of the Canyon Road Gallery, in Santa Fe; Jerrie Newsom

3, Ms. O'Keeffe's cook; and my father, William A. Thuma, an attorney, who wrote, on my behalf, a number of business letters to Doris Bry.

The correspondence is unique. I think it tells the story of the encouragement of a younger artist by a famous, well-known older artist. It also speaks of the intense exchanges, artistic and philosophical, that took place between these two artists, between Georgia O'Keeffe and myself -- sometimes a sharing of views, at other times an expression of different perspectives as to how "good" art, art that is true to the artist's integrity, can be accomplished. I spoke of it as "unique" in this sense: realize that little or none of it is part of the known cultural landscape of American art, of American art's history. Merely for what it reveals of Ms. O'Keeffe's spontaneous -- and deliberate -- attempts to aid a young artist, it deserves to be told.

Two women with so much to share, so many common bonds -- a love of the natural world in which each lived: Georgia O'Keeffe's "Pedernal," the high lands of New Mexico, M. Tuma's sprawling-with-rich-life-and-growth that she saw outside her studio window, in Guadalajara, Jalisco, Mexico, the earth that inspired her to create and visualize her sculptured forms and paintings.

There is sadness, too, in this correspondence: Of a rupture between these two women, and the end of a friendship. And the story of what brought that about and how each viewed and reacted to that separation between them -- especially the younger woman, myself, Mym Tuma, who grieved the loss of such a dear friend and, in some ways, a sustaining mentor.

Let the story be told. I have used these abbreviations to identify some of the writers: G.O. - for Georgia O'Keeffe M.T. - for Marilynn Thuma D.B. - for Doris Bry

|

MA Thesis Mural, 1964,

or, My Apotheosis

Inward knowing controls the freedoms we are -- and what

we stake -- then becomes action in life-time tension.

Published in Everyday Art, Volume 43, Spring 1965

I showed O'Keeffe a few snapshots of my MA mural that was called an Environment.(

click for Detail of the Mural)

"This is my first real creation. I can't explain it. I'm going to create those round shapes and find out what they are. But, my visit with you has gotten me started. I'm happy you had me come here to see you. I feel that I've made a step towards being a painter." Which is to say, I wanted verification in reality that what is, is. Coming to see her was part of the philosophy I had -- don't believe anything without observation.

"Last February, I had no preconceived idea about painting a mural, but I valued spontaneity and free flowing energy when I planned to tackle this really, really big project. Then inspiration eluded me. I walked back and forth in front of the blank pristine expanse of space and simply didn't know what to paint."

"She tried everything to solve the artist's equivalent of my novelist's dreaded writer's block," says my driver pal who had driven me weekly to the San Mateo dump with all my paint spattered floor coverings, coffee cans, and other detritus..

Did you try painting to music?" O'Keeffe interrupts, "Try it next time."

"Yes. I played classical music and paced the floor, waiting for a strong idea. What I got for my effort was a mammoth headache, so I drove to the store for aspirin. I explained my problem and its origins to the pharmacist and he sighed and said, "It's a little tedium vitae. "That's it!", I cried out, the tension of life! I raced back to the studio and completed the mural within months." Completing the mural was my epiphany.

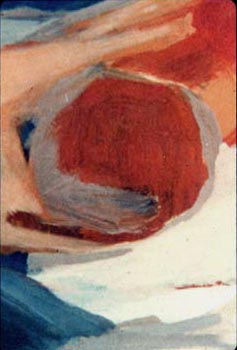

"An outpouring of saturated oil paint on gessoed plywood! Rivulets formed, areas congealed, and color flowed. Related shapes became apparent as the will to form dominated my mind.

"That spring of 1964 in the painting a particular shape appeared in the form of a spiral that I had never seen, a mysterious image to me. An orange-red form enclosed in a calm .. gray identified a new motion of a moving object among many other abstract, curving and spontaneous shapes of potential energy. "

"That spring of 1964 in the painting a particular shape appeared in the form of a spiral that I had never seen, a mysterious image to me. An orange-red form enclosed in a calm .. gray identified a new motion of a moving object among many other abstract, curving and spontaneous shapes of potential energy. "

"After growing up in a strong support network of friends and family, I am beginning to define my life, painting 'one-day-at-a-time,' responding to my inner voice. I decided to commit for a lifetime.

"Then, in a bookstore, in Art: U.S.A.

4 Now I read your statement:

'One works because I suppose it's the most interesting thing one knows to do. . . The days one works are the best days. . . I have no theories to offer.' "

"You defined painting as 'like the thread that runs through all the reasons for all the other things that make one's life' -- You confirmed what I found."

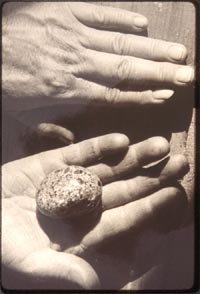

The First Pebble, NY [1965]

I took this contrasting idea of the pebble vs. the monument, brought it back

to the loft and from there formed The First Pebble. That resolution --

a rounded shell -- I found in the City.

I took this contrasting idea of the pebble vs. the monument, brought it back

to the loft and from there formed The First Pebble. That resolution --

a rounded shell -- I found in the City. -- Mym Tuma, From My Journals

Pebbles are sometimes rough shapes to look at shaped by the forces of nature, wind, rain, circumstance, fracture, depending on the substance of the rock they come from. So a pebble is a randomly shaped, unnamed circumstance and condition. It is a rudimentary form. I suppose that beginning this way the work had a strong, basic satisfaction.

Perhaps that is why I made the pebbles rather than raise a family.

In 1966, I talked to her about the slabs of the monumental towers and skyscrapers based on Mies van der Rohe, steel caged construction, the International Style that although sprang from the influence of the Bauhaus, ironically caused alienation. How I needed to escape Manhattan for freedom of space and to have clear sight. That's why I took the subway to the Bronx to see things and walk around. In spring I found Anne Gibbs' "sense of freedom."

5

I came upon a gateway to Mount Hebron Jewish cemetery and entered to find a custom expressed of placing rounded pebbles on monument which were softened forms placed on the manufactured slabs of granite." My voice ended in a whisper. I could see the look in O'Keeffe's eyes, as she began to see the significance of what I was telling her.

I came upon a gateway to Mount Hebron Jewish cemetery and entered to find a custom expressed of placing rounded pebbles on monument which were softened forms placed on the manufactured slabs of granite." My voice ended in a whisper. I could see the look in O'Keeffe's eyes, as she began to see the significance of what I was telling her.

"Thinking back on my life in New York City, it gave me a start, all I needed to go forward. Return to the land was the next step; it had to be because there was no compromise with the City -- no way to function. I couldn't hear the rhythms of night and day -- I couldn't smell them nor sense them living in an artificial surrounding and I wanted to return to the sea, to the country."

New York City was a maze of monuments from which I exited carrying my "First Pebble" in my strong hands. "Pebbles are a new direction; valid, organic and as fundamental as nature itself though infinitely personal and essentially spiritual."

6

Then I knew our conversation should stop. --- It was time for me to leave.

One on One Visit 1966

The Mushroom

Forms in relief are defined by space and by light. That's true

of the landscape everywhere I've seen it.

-Mym Tuma, The Montara Album [1966]

"You haven't been here before, have you?" she said. Surprised, I answer, "I first came here in June of '64, two years and four months ago." "You haven't been here before, have you?" she said. Surprised, I answer, "I first came here in June of '64, two years and four months ago."

Inside her house, we spoke again for hours and hours. Through-out the day she and I had a central theme to our conversations. I, that round or sculptural forms in painting did more genuine service to what we saw in nature; she, that she had been served well by being a painter concerned with the pictorial or the canvas as surface for the profound aspects of nature that she saw in her New Mexico mountains. Back and forth we would go on this issue. I sought to introduce her to my idea of Pebbles. She, in turn, would reply:

"I never worked from theories, they never worked for me." "What do you mean? I continue, "This idea is living for me. I've been able to draw, then shape relief forms, like the one I call The Mushroom." I widen my arms to show her the size of the oval form, 24 x 18, expanding in space as if

against the wall explaining that the proof is in my photographs.

She unfolds my recent letter and two prints drop out. One of them she picks up and hands me

the other one. "May I have this one?" she asks of a photo of The Mushroom. "Oh, yes, you may

keep it," I reply. "Why did you make that?" she asks pleased with herself. "In New York, I began experimenting to find a synthesis of painting and sculpture. The round autonomous shapes in my mural began to emerge and become three-dimensional. They referred to something that existed in time and space and I wanted them to be there," I told her.

"I began by drawing forms that are expanding into space from the wall, but relate to it, like that raffia basket hanging over there. I've experimented to go beyond the illusion of painting on a flat surface like that," I say glancing behind her at the painting on her easel. It consisted of a few weak tracings in pencil wandering off the edges in a map like a view of the land. But she was there when the canvas was white, she hadn't finished it yet. "My idea is living for me! What do you mean? Then you don't work from a theory?"

"No I don't. So I couldn't talk about it. . . I had other ideas of my own, you know. You can't learn from a formula for painting. The men Stieglitz showed at '29l' dared me to paint, and then I did and they learned from me! -I don't identify my style with anybody but myself."

In her day the men were always the intelligent talkers, and as a student she would wait down the

hall from them as an outsider. For the primary world was observation rather than theoretical discussion. Since her own work was primarily from observation and was suspicious of words, she saw herself as a woman of action: the goddess. She had to, with all the emotional pictures Stieglitz made of her body. Here was a woman before me who had set the art world off into a new orbit, a woman whose talent met or exceeded her famous husband's. Her single-minded devotion to her own eyes view of her world presented her private, inner thoughts to future generations of art.

[1] Laura Gilpin, "The Austerity of the Desert Pervades Her Home and Her Work,"House Beautiful , April, 1963, pp. 144-148. The bleached skull photographed for this article, was one of the objects we exchanged. G.O. handed me this particular Ram's skull with curving horns that had hung over her gate for 30 years. She noted it was brittle, as she gave it to me as a memento of our relationship when I left in 1971.

[2] Henry Hanson quoted from O'Keeffe's first letter to me in "Art Works," Chicago Magazine , March, 1988 [Vol. 37, No. 3], p. 21.

[3] Jerrie Newsom, employed as a housekeeper at the ranch, during the summers of 1964-73, was among the non-art friends on the periphery of G.O.'s life, working as her chauffeur, nurse and confidante.

[4] Lee Nordness, Ed., Art USA: NOW, 1962. G.O.'s quote was: "One works because I suppose its the most interesting thing to do..." At that time I had just established my commitment to paint for my lifetime. She went on to define painting as "the thread that runs through all the other reasons for all the things that make one's life," a precept which continues to guide me even today.

[5] Letter to the author, from Anne Louise Gibbs, Assistant Professor of Art, Interior Architecture & Design, Northwestern University, 1965, "Marilynn, you must not get discouraged about your paintings. You are now going through what I generally refer to as the "drudge phase." The true artist always goes through this phase...you have questions regarding the nature of art...your concept of reality...your relationship towards society...your attitudes towards yourself, emotion and freedom....Continue to seek the best minds for criticism for your paintings...in this way you will grow."

[6]Sculptor Earl C. Neiman, in a letter to the Louis Comfort Tiffany Foundation, dated April 26, 1965, wrote, "Through hard work, an incredible sense of form, an affinity with and love for the natural, and fortified with the courage to stand free of trend or outside influence, Marilynn has made a discovery in her work which this observer considers a real breakthrough. She has something important to contribute to art and her "pebbles" are a new direction; valid, organic and as fundamental as nature itself though infinitely personal and essentially spiritual. Hers is the purest art I have seen.

The commitment Marilynn Thuma has made of her life to fundamental values and her preoccupation with the problem of form that confronts the artist of passion when he or she attempts to penetrate the concrete with the delicate instruments of the spirit deserves the support of any foundation established to encourage the "authentic artist."

|

Text written by Mym Tuma, Southampton, NY 11969

Text written by Mym Tuma, Southampton, NY 11969

All Rights Reserved © Bernard Gotfryd of East Hampton (O'Keeffe, 1970)

Text & Images © 2004-2010, All Rights Reserved

Site By:

Hamptons Online

|